It was an odd thing for the two national newspapers to focus on. Both The Australian and The Australian Financial Review decided that the most important thing to come out of the Australian Energy Market Operator’s scenario planning for the future grid released on Friday was the assumed absence of a carbon price.

AEMO decided, the two papers noted, that it could not factor in a carbon price in its Integrated System Plan because it was not clear there would ever be one, thanks to the intransigence of the Coalition.

But it’s not really up to AEMO to decide what mechanisms should or should not be in place. In the end, there is more than one option, particularly given the cost of renewables has fallen to the point where it really doesn’t need to have new subsidies.

All the transition to renewable really needs is a plan, and a vision. And, finally, as we reported on Friday, AEMO is going to produce one as part of its ISP, which is its 20-year blueprint for the future grid.

That was the big story that was not mentioned by either The Australian or the AFR in their reports, possibly because it is antithetical to what they – and the current government, for that matter – believe is possible: AEMO will lay out a detailed plan on how to almost completely decarbonise the Australian grid by 2050. And it is hugely significant.

Over the past 10 years, there have been numerous studies about whether Australia could reach 100 per cent renewables, including by AEMO itself (somewhat reluctantly at the time in 2013), and by universities such as UNSW and ANU, the CSIRO (in conjunction with the networks lobby), and by NGOs such as Beyond Zero Emissions.

Those studies, however, looked at 100% renewables at a point in time. This new work by AEMO, part of the updated Integrated System Plan to be finalised next year, is a plan on how to get there, or close enough, including the infrastructure, rule changes and investment required to ensure there is enough capacity, storage and modes of delivery to keep the lights on.

And that is what makes AEMO’s work so important. This is no theoretical exercise. AEMO’s prime responsibility is to ensure secure and reliable supply. But as it notes in its recent annual report, its mission is also to plan for the future. Governments might have given up on that idea, but thankfully not AEMO.

The so-called “step change” plan is one of five different scenarios to be modelled by AEMO in its forthcoming ISP.

One will be the horror show that assumes that we go even slower with the transition than we are now; that Victoria and Queensland repeal their targets and the federal government drags its heels and erects barriers to new technologies and extends the life of coal. By implication it assumes that the Coalition – and its rejection of climate science and its support for coal – rules supreme at state and federal level.

The central scenario assumes business as usual – effectively those current policy settings at federal and state level. But then it starts to get interesting: What happens if technology and economics take the transition beyond that – either through a consumer-led uptake of things like rooftop solar, household batteries and electric vehicles, or a technology led transition at grid scale?

Finally, there is the step-change scenario, the only one that acknowledges both the science on climate change and what Australia and 193 other countries signed up to do in Paris – keep average global warming to well below 2°C and hopefully below 1.5°C.

The step-change scenario to be outlined by AEMO is the only one that conforms to that target. AEMO says it will be consistent to limiting temperatures to between 1.4°C and 1.8°C. It would, of course, need some additional policy mechanisms, but it doesn’t have to be a carbon price. It could be auctions, or mandates. That will be for future governments to decide.

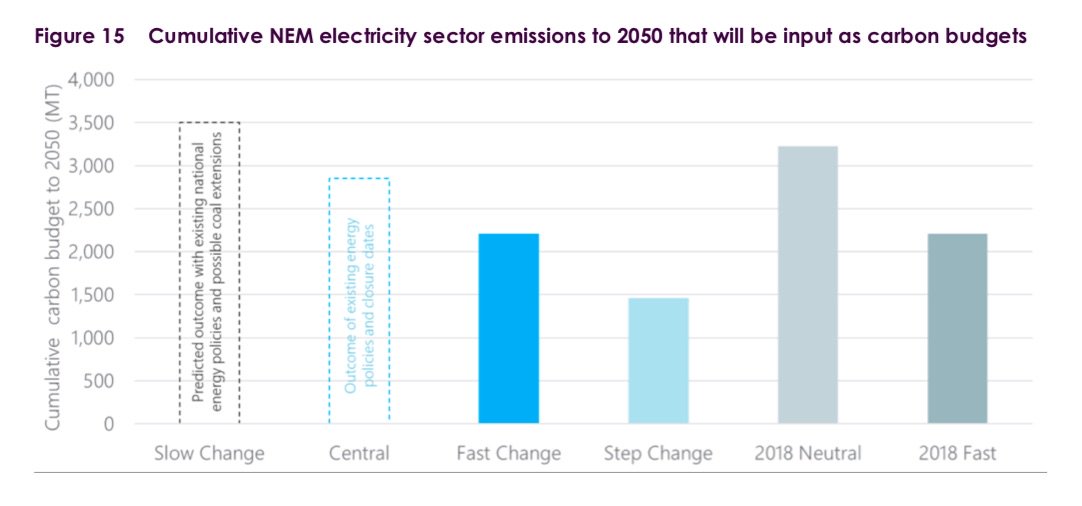

The other scenarios leave Australia well short. Pointedly, AEMO notes that current policies (including the Labor states) leave the country well short as it fits into a scenario of around 3.5°C. Even the faster transitions led by consumer and technologies leave Australia short at between 2.5°C and 3.5°C.

That’s what makes the “step change”, which is based around the “carbon budget” used by the UN, and advisory bodies to so many international governments, including the unheeded Climate Change Authority, so important.

This graph above shows just how much of a step change it is from previous thinking; compare the lift blue line in the middle with the dark blue “fast change” scenarios from the new ISP, and last year’s version (on the right). And these are cumulative carbon budgets out to 2050, not just the end point.

And as AEMO says in its recent three-year corporate plan, the pace of technology change and the country’s unique resources in wind and solar and technical know-how put Australia in a unique position, even if the quality of the political and mainstream media debate don’t always make that clear.

“The rapid changes occurring in the Australian energy environment, the size of our energy grids, the changing supply availability and mix of our portfolio of gas and power resources and relative sparseness of our population, place AEMO in the unique position of having to solve technical challenges that our peers in other jurisdictions are just beginning to see or, due to population density and interconnected power systems, may never see,” it notes.

“However, we are optimistic that the rapid technological changes that are occurring in the Australian energy system, and the natural resources we have, can also become an advantage to consumers provided that there is a desire and willingness to pursue actions that achieve these benefits.”

Note those words, co-authored by AEMO chair Drew Clark – the former secretary of the department of energy, and former chief of staff to prime minister Malcolm Turnbull – and CEO Audrey Zibelman: “Provided there is a desire and willingness to pursue actions etc etc.”

This is not just about policy and political will. In that report, AEMO notes the “legacy systems” and cultural issues that need to be overcome, including within its own organisation.

But AEMO is not the only institution working to the future. The Energy Security Board is looking at a complete re-write of the rules of the electricity market, in recognition that the system is changing, and needs to be changed.

The CSIRO is also working on updating its “GenCost” publication, which last year stated unequivocally that the cheapest form of new generation investment was wind and solar, backed up by varying levels of storage.

That new work will be crucial in showing what the energy transition may cost, and where investments may best be made. CSIRO will be focusing on the renewable energy technologies, including offshore wind, and is developing more sophisticated way of valuing and costing storage.

Coal will be downplayed, because no one has even a half-serious proposal to do something new. As AEMO notes in its scenarios report: “Given the market need for flexible plant to firm low-cost renewable generation, new coal generation would be highly unlikely in any scenario with emissions abatement objectives, particularly given the long-life nature of any new coal investment.”

And in recent stakeholder consultations, not one person mentioned nuclear, despite the proliferation of government inquiries. That remains a fantasy, and a sign of the hurdles ahead.

Of course, the next iteration of the ISP will not be the final word in how the transition to a renewable grid can be achieved. More work will need to be done on new technologies such as hydrogen, and there will be new thinking about meeting challenges such as system strength, voltage and inertia.

As has been seen in recent months and years, AEMO itself is on a learning curve, as is the industry, with the core technologies of wind and solar and batteries and pumped hydro supplemented by smart software, artificial intelligence and new learnings about system security.

And others are also on the case. UNSW and the Climate and Energy College, along with ITPower, are also releasing a sophisticated planning model that will allow others to play with different scenarios, and this will be regularly updated to shine the light on the future, and help guide the likes of AEMO.

Finally, Australia will have something to work with, a coherent strategy and a greater chance of delivering a cheaper, cleaner and smarter grid.