The response by Europe and the US to Moscow’s military offensive in Ukraine will be painful for consumers, but it will eventually reshape the energy world ― and not to Russia’s gain. The Arab world and all oil and gas exporters, need to be prepared.

Berlin, Brussels and Moscow forged their fetters from the start of Soviet gas sales to Austria in September 1968, the month after the crushing of the Prague Spring. The idea of energy trade to discourage war was a good bet on the self-preservation instincts of Soviet apparatchiks, but has succumbed to what many see as new adventurism.

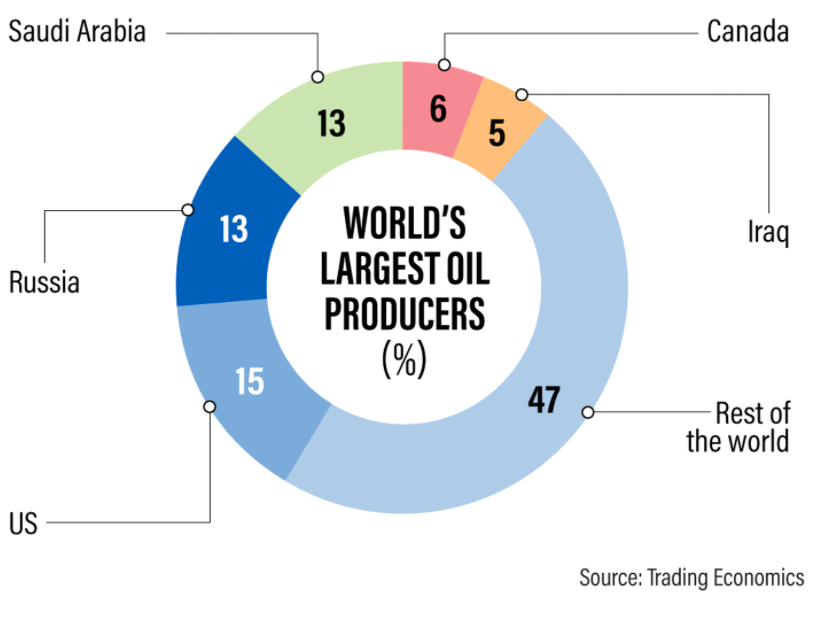

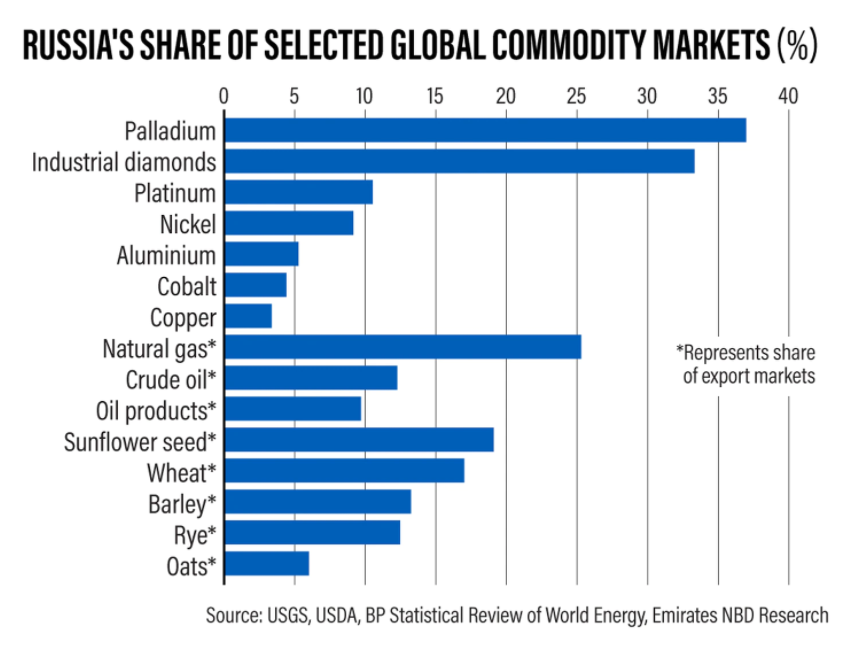

The European Commission’s new strategy, shown in leaked drafts, aims to reduce, then eliminate dependence on Russian fossil fuels. Russia accounts for 25 per cent of world gas exports, nearly all to Europe, 18 per cent of coal sales, and between 11 to 13 per cent of oil exports, about half of that to Europe.

In comparison, the September 1973 oil embargo launched by a group of Arab petroleum exporters cut world production by only 7 per cent, was over by March 1974 and did not affect other fuels. Yet it severely damaged the world economy, hugely boosted energy efficiency, led to the rise of nuclear power, the early days of solar and wind and created the modern energy security architecture.

Now, the combined effects of sanctions, informal bans, war disruption and Russian counter-measures will be titanic. At risk are supplies not just of fossil fuels, but fertilisers, food, aluminium, metals used in batteries and electrolysers, and nuclear fuels. A steep global recession is likely.

From a mix of war disruption, policy, economics, caution and moral suasion, Russia will cease over this decade to be an important energy supplier to Europe. Mr Putin has launched this offensive at a bad time: the move for decarbonisation, and the rising viability of low-carbon technologies, already posed a severe threat to his country’s fossil fuel exports.

Opec+, which of course includes Russia, chose on Wednesday to hold to its regular plan of increasing oil production targets by 400,000 barrels per day each month. It did not see physical supply disruptions yet. But those are clearly coming, through sanctions. The group will soon have to decide whether to unleash its unevenly distributed spare capacity or risk a colossal price spike followed by demand destruction.

Russia’s own output will slump as it can no longer access the funds and technology for more challenging frontier fields. Its remaining sales will reorient towards China and other Asian countries, competing more with the Gulf, but opening up its traditional space in Europe.

In January, Saudi Aramco bought a stake in Poland’s second-largest refinery, promising to supply almost half the country’s oil. Saudi Arabia and other Arab oil producers with plans to expand capacity will find ready markets.

Overall, though, Europe will dramatically accelerate its efforts to get off petroleum. That will drive forward electric vehicles and hydrogen worldwide. Gulf oil exporters can expect a very good few years, but this crisis sharpens the threat of peak oil demand.

As my colleague at the Columbia Centre on Global Energy Policy, the sanctions specialist Richard Nephew, suggests, permitted Russian oil (and gas) sales to Europe could be ratcheted down over time. That would allow the market some time to adjust. It would guarantee a growing quantity of non-Russian gas imports, effectively underwriting new supply.

Or similarly, Europe could impose steep tariffs on Russian gas to prefer all other sources first and retain much of the resulting revenue. The vast bulk of Gazprom’s exports have nowhere to go but Europe – much smaller amounts to China flow from different fields in east Siberia.

The International Energy Agency has laid out a ten-point plan that would reduce Europe’s gas imports from Russia by a third this year. This includes alternative supplies, greater energy efficiency, more renewables and nuclear, and conservation by consumers. Several other studies show how the need for Russian gas could be eliminated entirely before 2030.

Turkey is a key node. The supply from Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey and on to Greece and Italy faces a threat from Russian troops ensconced in Georgia’s occupied region of South Ossetia. Its mountains are not far from the gas pipeline south of the capital Tbilisi and Gori, home town of Josef Stalin, “the broad-chested Ossete” as he was dubbed by poet and Gulag victim Osip Mandelstam.

But Turkey has found sizeable gas reserves in its part of the Black Sea. Last month, president Recep Tayyip Erdogan met Nechirvan Barzani, president of Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan region, and expressed interest in Kurdish gas. A pipeline is already under construction almost to the Turkish border. From there, it could displace Russian supplies in Turkey and flow on to south-eastern Europe.

The huge boost required in European liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports – a potential 60 billion cubic metres per year in the short term, 160 bcm in the longer term – is equivalent ultimately to about a third of the existing world LNG market. That is a giant prize for Middle Eastern countries that can increase LNG exports, notably Qatar by the 2025-27 period, but also the UAE and possibly east Mediterranean.

Not a molecule of Russian hydrogen is ever going to enter the EU now. For Gulf countries, which have begun building their energy strategies around exporting this clean future fuel, a big potential competitor has just knocked itself out. The demand for low-carbon hydrogen to replace oil, gas, coal in steelmaking, ammonia in fertiliser manufacture – will accelerate dramatically.

Even if the Ukraine conflict ends soon, the shock has already rewired thinking on diplomacy, the military – and energy. The future looks cleaner, safer, and wealthier. To get there, the world first needs to avoid catastrophe.